In May, I attended the global summit of the International Community of Mennonite Brethren (ICOMB) in Brazil. Following the event, Emerson Cardoso, Brazilian church leader and Multiply’s Regional Team Leader for Latin America, took seven of us to visit the Ribeirinhos, the “River Folk” of the Amazon. For the past several years, Brazilian MBs have been involved in church planting initiatives among this indigenous people group as the Ribeirinhos respond to the Gospel. Our international group consisted of: Johann Matthies (Germany), Valdas Vaitkevi?ius (Lithuania), Walter Jakobeit (Germany), Jaeem (South Asia), Franz Wolf (Brazil), and Scott and Nikki White (Canada).

After flying overnight from Curitiba to Manaus, we drive long hours along a sketchy, desolate road to some obscure town on the banks of the Rio Negro, then travel even longer hours by boat. I gawk at monkeys, giant lily pads, pink dolphins, massive ant colonies and exotic birds, with only an occasional boat to hint at hidden civilization in the otherwise unbroken seascape of this massive branch of the Amazon River.

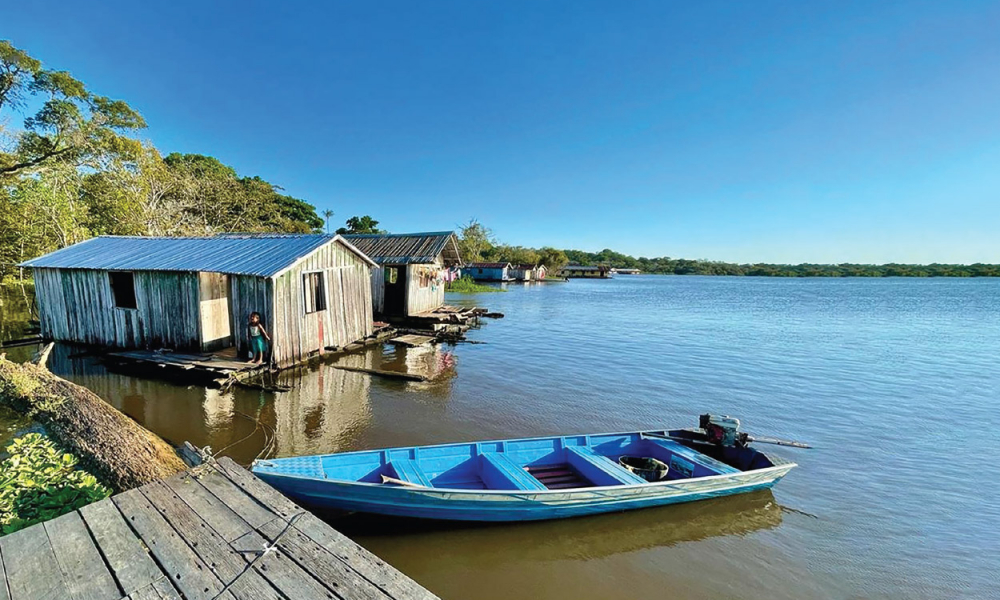

After hours on the river, I feel my smallness: an insignificant speck of humanity on a vast and untamed canvas. We wind through tributaries where the dense vegetation and trees are half-submerged by waters that can span up to forty kilometers. Rounding a bend, a village suddenly appears. Are there really people living here? Don’t they get lonely? “Of course, they are lonely!” Emerson replies. “Why else do we come? To show that we care, we see them, God sees them.”

The River Folk greet us with friendly reserve, slightly taken aback when our outgoing South Asian friend stages a photo shoot. Are we offending them? “Don’t worry,” Emerson assures us, “We are invited guests. Otherwise,” he adds wryly, “they have a legal right to kill us.” Hospitality, it seems, has strict parameters in the Amazon.

As our team spreads out, I see an elderly, dignified matriarch sitting somewhat apart from the rest. We smile, and soon we are swapping stories, mom-to-mom. Nineteen? Slack-jawed, I try to imagine birthing that many children in one lifetime. “And thirty-two grandchildren,” she adds, “to keep me company. You?” Woefully deficient in fertility, I confess, admiring the one big extended family which comprises her entire village.

The villagers prepare a feast: slabs of two-meter-long pirarucu fish baked in banana leaves, exotic fruits, vegetables from their garden, and chunks of savory meat from the paca—inelegantly described as a large rodent. I am invited into the chieftain’s house, where she tells me that eight of them live in this cramped, rustic hut. Where do they all sleep? She points to eight bundled hammocks, pegged to the ceiling. When I tell her that my husband and I sleep alone in one room, she is sad for me.

After lunch I ask some children about bathroom facilities. They shrug and point casually into the jungle. I wander the path uneasily, recalling words of half-joking warning from our guide: “Avoid hanging vines (snakes drop from them…)”, “look before you pee (ants swarm; they destroyed a whole town…)”, “watch for logs that move (alligators…)” and, above all, remember, “Everything here wants to kill you.”

The time to depart comes all too soon, as our captain does not want to be on the river at night. The piranha fish, he explains, feed only at night. The villagers walk with us to the shore, graciously extending an invitation to return. In turn we invite them to own homes, far away. “Too far!” they say, shaking their heads. Will we come back? I fervently hope so. We had come as guests of the River Folk, but we were leaving as friends.